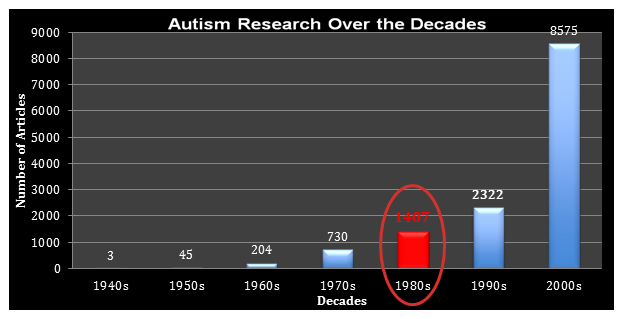

The 1980s

Highlights

• Autism classified as a developmental disorder in DSM-III

• New methods of diagnosing autism:

o CARS replaced Rimland, Creak, Kanner criteria

o ICD-10 diagnostic algorithm

• Prevalence: 2–5 per 10,000 people

• Affective and cognitive theories proposed

• Lovaas technique developed

| 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s |

Research in the 1980s

In the 1980s, autism was classified for the first time as a developmental disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM-III), a manual published by the American Psychiatric Association to set standardized language and criteria for describing mental disorders. This allowed doctors to accurately diagnose autism and to differentiate autism from schizophrenia. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) was published, encompassing the criteria of Leo Kanner and E. Mildred Creak of Maudsley Hospital in London.[1] CARS was considered to be the gold standard for diagnosing autism. The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) criteria, a diagnostic algorithm, was also developed. In a sample study of 32 subjects, this algorithm accurately diagnosed the 16 patients with autism and the 16 non-autistic patients.[2]

In the 1980s, autism had a prevalence of about 2–5 per 10,000 people. There was a male:female ratio of 3:1, and research showed that autism was familial, with genetic heterogeneity.[3] One study determined a deficit in the development of nonverbal skills, indicating that behavior was a significant characteristic in young children who receive the diagnosis of autism.[4]

One study proposed two different theories: the affective theory and the cognitive theory. The affective theory states that those with autism are not able to understand the emotions of others, whereas the cognitive theory predicted the particular pattern of impaired and unimpaired social skills in children with autism, as well as the pragmatic deficits.[5]. The affective theory applied the results from emotional recognition tasks better the cognitive theory did. Scientists questioned whether children with autism had a “theory of mind” where they find it difficult to understand things (e.g., behavior, emotions) from any perspective other than their own and differentiated autism from mental retardation.[6] In addition, O. Ivar Lovaas of the University of California, Los Angeles, developed an intensive behavioral treatment technique for young children with autism, which improved their cognitive abilities.[7] A study in the Nordic countries concluded that autism sometimes had a hereditary component and that perinatal stress was implicated in some cases.[8]

Ross Senter, Karthik Kumar, and Sharmila Banerjee-Basu, Ph.D.

| References: |

|