The 1990s

Highlights

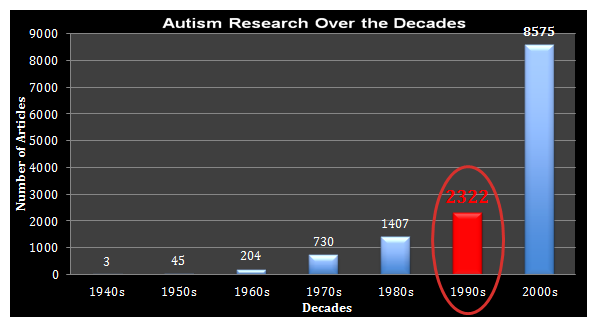

• Public awareness of autism heightened and autism research increased dramatically

• Scientific and empirical approach encouraged

• Autism Diagnostic Interview revised

• Prevalence: 18.7 per 10,000 people; need for special services for children

• Genetic studies expanded

| 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s |

Research in the 1990s

Public awareness about autism heightened in the 1990s, and autism research increased dramatically. The Center for Autism and Related Disorders, the National Alliance for Autism Research, Cure Autism Now, and the Southwest Autism Research and Resource Center were all founded. A scientific and empirical approach to autism research was encouraged. Reported cases of autism significantly increased, reflecting a better understanding of the disorder’s symptoms.

The Autism Diagnostic Interview underwent a major revision.[1] It is a procedure closely related to the criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10), a World Health Organization document.[2] The revised version was reorganized and modified to be appropriate for children starting with a mental age of 18 months.[1] Previous studies had shown that the median prevalence of autism in a group of 10,000 people was 5.2; however, a minimum prevalence of 18.7 per 10,000 people was now reported, suggesting a need for special services for a large group of children.[3]

Autism was now thought to extend beyond its traditional diagnosis, with several genes affected.[4][5][6][7] If a sibling was diagnosed with autism, there was found to a 12.4–20.4% chance that a sibling would exhibit a lesser degree of an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), part of a range of psychological disorders characterized by some degree of abnormalities in communication and social interactions as well as repetitive behavior within very restricted interests. Abnormalities in the fetus were suspected to cause autism.[4][5] In one study, 22 children, 11 with autism and 11 neurotypical, were videotaped during their first birthday parties.[8] The tapes showed that four behaviors correctly classified 10 out of 11 children in each group. The behaviors observed were pointing, showing objects, looking at others, and responding to name.

One genetic study was of 51 autism multiplex families.[8] This was a case in which paternal inheritance led to a normal phenotype and maternal inheritance led to autism or atypical autism.

Ross Senter, Karthik Kumar, and Sharmila Banerjee-Basu, Ph.D.

| References: |

|