The 2000s

Highlights

• Children’s Health Act signed

• Autism Speaks founded

• Research progresses rapidly

o Main areas of research involve studying genetics and using new technologies

| 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s |

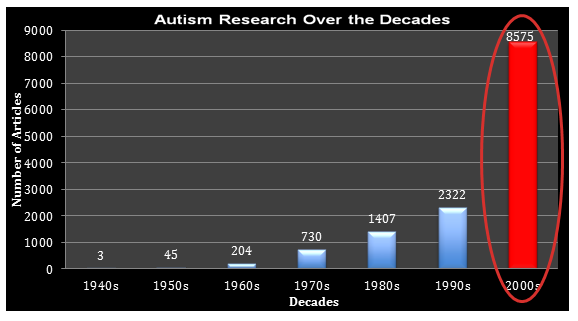

Research in the 2000s

In 2000, the Children’s Health Act was signed into law, providing funding for a long-term research study on autism and establishing an autism research coordinating committee. The decade also marked a period of rapid advancement in autism research. In addition, the Organization for Autism Research and Autism Speaks were founded to garner support for research and provide information to the public. In 2000, the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule–Generic (ADOS-G), an algorithm for assessing individuals suspected of having autism, was developed.[1]

Research focused mainly on the genetic basis of autism. With the advent of newer and more powerful biomedical technologies, understanding the role of genes in neurodevelopmental disorders quickly became the primary goal of many researchers.[2] Studies showed that children with autism had more de novo copy number variants (CNVs) than their non-autistic counterparts.[3] This was a major advance in understanding the genetic basis of autism. Methods for detecting CNVs were more powerful than traditional gene-mapping to identify gene risk factors in autism.

Researchers found that mutations in two X-linked genes encoding the neuroligins NLGN3 and NLGN4 affected cell-adhesion molecules localized at the synapse. This suggested that “a defect of synaptogenesis may predispose to autism.”[4] Another study reported the association between microdeletion and microduplication on chromosome 16p11.2 with autism.[5] Other genetic-related research found that a mutation of a single copy of the gene SHANK3 on chromosome 22q13 could result in language and/or social communication disorders.[6] One genome-wide scan found evidence for linkage of markers on chromosomes 5 and 8 to autism and Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD).[7] Another study suggested that cytogenetic and microarray analyses should be part of routine clinical workup, after the discovery that structural variants were strongly correlated to ASDs.[8]

In the past decade, the prevalence of autism was slightly higher than in the 1980s or 1990s; however, the numbers were consistent with similar studies conducted in the early 2000s. The male-to-female ratio dropped from 4:1 to 1.3:1.[9]

Ross Senter, Karthik Kumar, and Sharmila Banerjee-Basu, Ph.D.

| References: |

|